The National Institutes of Health has awarded the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation $3.7 million to continue research on Sjögren’s syndrome, an autoimmune disease.

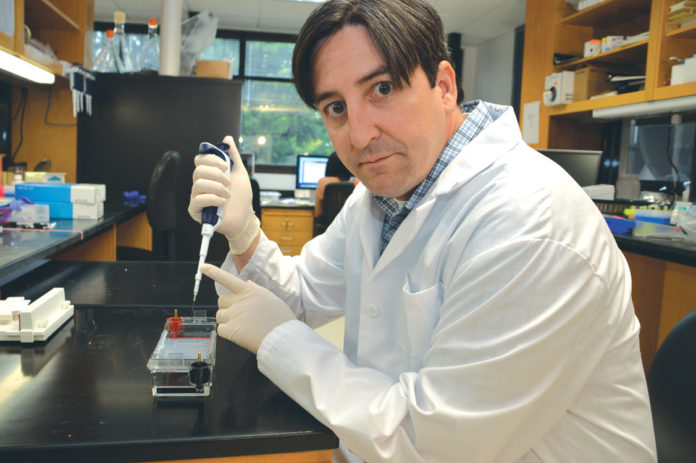

OMRF scientist Christopher Lessard, Ph.D., received a five-year grant to identify genes associated with the disease. The work will aid in the development of strategies to diagnose and treat the condition.

In Sjögren’s, immune cells attack moisture-producing glands, causing painful dry eyes and mouth. It can result in irreversible tissue damage and complications like neurological problems, lung disease, and cancer. There is no known cure for the condition, which disproportionately affects women and is estimated by the American College of Rheumatology to affect as many as 3.1 million people in the U.S. (story continues below)

· Three years’ experience working as an RN in assisted living or similar facility

· Achieve and maintain compliance for all OK. State Dept of Health regulations governing long term care facilities

· Complete working knowledge of all applicable laws and regulations

· Experience performing routine assessments

· Strong managerial skills

· Implement recommendations to improve all facets of the Nursing department

· Active Oklahoma RN license

· Willing to re-locate and/or live in the Stillwater area

Work in a positive team environment with leaders who value our staff and have the chance to make a difference in the lives of those we serve.

Golden Oaks Village offers competitive pay, insurance benefits, 401k and paid time off.

Apply on-line at www.companionhealth.net

“Current treatments for Sjögren’s only address its symptoms, and just diagnosing the disease is notoriously difficult,” said Lessard, who’s been studying Sjögren’s at OMRF since 2007. “It shares features with many autoimmune diseases. This can lead to misdiagnosis, which ultimately makes studying the disease challenging.”

The grant will allow the researchers to collect and analyze more than 10,000 DNA samples donated by Sjögren’s patients from around the world. The samples are available thanks to the OMRF-led Sjögren’s Genetics Network, or SGENE, an international network of 26 research groups dedicated to identifying the genes associated with the disease. “Thanks to these international efforts, we’ve pinpointed 20 genes associated with Sjögren’s in recent years. But we suspect there are many more. In contrast, scientists have identified more than 150 genes associated with lupus, which is another related autoimmune disease,” Lessard said.

At OMRF, researchers will use biopsy tissue samples to determine how genetic variations in Sjögren’s might change the regulation of genes associated with the disease.

Lessard hopes to separate patients into sub-groups based on individual characteristics of their disease, develop better clinical tools to diagnose patients earlier, identify patients at high risk for cancer and other serious complications, and identify existing medicines to treat the condition by associating the disease to genes involved with other conditions.

“This ambitious work will result in the largest genetic study of Sjögren’s to date,” said Patrick Gaffney, M.D., head of OMRF’s Genes and Human Disease Research Program. “By combining analyses of genetic factors, we should have a much clearer view of the underlying causes of this puzzling disease.”

The work is funded by grant number R01AR073855 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, a part of the NIH.