For Broken Arrow’s Madison Cain, Santa only needs to leave one thing under the tree in 2020: A new Bitty Baby.

Madison’s love of the popular line of dolls is fitting: Born full term at 5 lbs., 9 oz., she was a bitty baby, too. When she seemed to stop growing after her first birthday, doctors chalked up her short stature to simply being small for her age.

But by the time Madison was in kindergarten, she had endured broken bones, impaired mobility, cataracts and crippling digestive issues. At 6, to help her gain weight, she got her first feeding tube. Through it all, no one could tell Melissa and Clifton Cain why. Their daughter was a mystery. (story continues below)

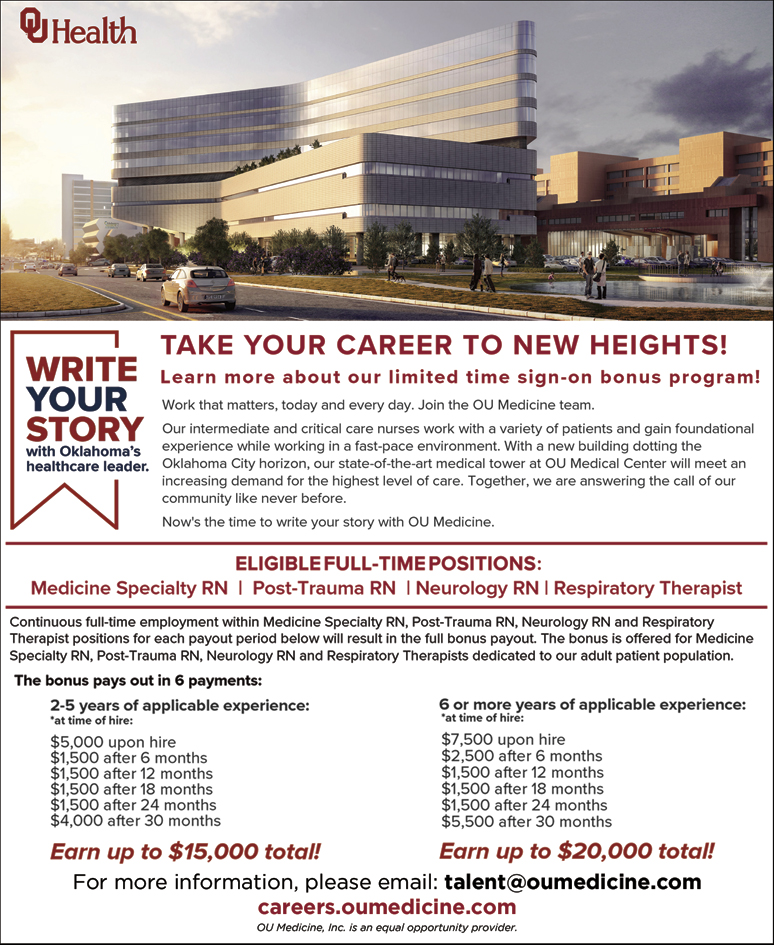

WRITE YOUR STORY with Oklahoma’s healthcare leader.

Learn more about our limited time sign-on bonus program!

Work that matters, today and every day. Join the OU Medicine team.

Our intermediate and critical care nurses work with a variety of patients and gain foundational experience while working in a fast-pace environment.

With a new building dotting the Oklahoma City horizon, our state-of-the-art medical tower at OU Medical Center will meet an increasing demand for the highest level of care.

Together, we are answering the call of our community like never before. Now’s the time to write your story with OU Medicine.

ELIGIBLE FULL-TIME POSITIONS:

Medicine Specialty RN | Post-Trauma RN | Neurology RN | Respiratory Therapist

https://oumedicine.wd5.myworkdayjobs.com/en-US/OUMedicineCareers/job/Oklahoma-City/RN—Registered-Nurse—Medicine-Specialty_R0005014

https://oumedicine.wd5.myworkdayjobs.com/OUMedicineCareers/job/Oklahoma-City/RN—Registered-Nurse—Post-Trauma—Days_R0005389-1

https://oumedicine.wd5.myworkdayjobs.com/en-US/OUMedicineCareers/job/Oklahoma-City/RN—Registered-Nurse—Neurology—FT–Nights_R0005100

https://oumedicine.wd5.myworkdayjobs.com/en-US/OUMedicineCareers/job/Oklahoma-City/Respiratory-Therapist-RRT—OU-Medical-Center—Nights_R0004682

Continuous full-time employment within Medicine Specialty RN, Post-Trauma RN, Neurology RN and Respiratory

Therapist positions for each payout period below will result in the full bonus payout. The bonus is offered for Medicine

Specialty RN, Post-Trauma RN, Neurology RN and Respiratory Therapists dedicated to our adult patient population.

The bonus pays out in 6 payments:

2-5 years of applicable experience:

*at time of hire:

$5,000 upon hire

$1,500 after 6 months

$1,500 after 12 months

$1,500 after 18 months

$1,500 after 24 months

$4,000 after 30 months

Earn up to $15,000 total!

6 or more years of applicable experience:

*at time of hire:

$7,500 upon hire

$2,500 after 6 months

$1,500 after 12 months

$1,500 after 18 months

$1,500 after 24 months

$5,500 after 30 months

Earn up to $20,000 total!

For more information, please email: [email protected]

careers.oumedicine.com

OU Medicine, Inc. is an equal opportunity employer.

After years of dead ends, the Cains turned to specialized genetic testing. That Hail Mary gave them an answer: Their daughter had a mutation in a gene known as MBTPS1.

A geneticist analyzed the results and told the Cains there was just one published study in the world on the mutation. It involved a single patient, “But,” the doctor said, “It’s not what Madison has.” Unsatisfied, Melissa Cain — a nurse practitioner — found the research paper. “It wasn’t a perfect match, but I knew there was something to it, some connection,” she said.

When she looked up the contact information for the author, Cain couldn’t believe what she saw. He was 100 miles away, just down the Turner Turnpike at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation.

At OMRF, Lijun Xia, M.D., Ph.D., Patrick Gaffney, M.D., and two other scientists had started to unravel this genetic mystery two years earlier. They were the first to identify the condition, a skeletal disorder now known as spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, Kondo-Fu type (SEDKF), in a single patient from Yukon, Sydney Rutz.

Until Cain emailed Xia, the researchers thought Rutz was one of a kind. After meeting Madison and confirming she had the same condition, they expanded their search for SEDKF patients to learn more about the rare disease and find therapies to help.

“You work in a lab with mice and test tubes, and sometimes you become desensitized to the real problem,” said Xia. “But once you see the patient, it makes you think how your research can help solve a real problem. It gives you more motivation.”

Xia’s team has now identified eight more patients around the world. He wants to test an existing medication that he believes — based on work he’s done in his lab at OMRF — could help children with SEDKF. But that requires a clinical trial with dozens more patients to assess its efficacy and safety in a rigorous, controlled way.

Xia has launched a website for doctors to use as a resource. A group of researchers now reviews case information as it arrives, all working together to someday help patients with SEDKF.

With genetic diseases, Xia said, the need for therapies is especially profound. “These patients will live with their conditions for life.”

Still pint-sized at 3 feet, 6 inches tall, Madison, now 8 and a second grader at Anderson Elementary in the Tulsa Union district, gets an infusion every six months to help with her bone density and has reduced her tube feedings. She’s stronger, thanks to physical therapy, and has more energy.

Although it was different not to see their extended family for Thanksgiving because of the pandemic, Madison said there was a bright side: She got to decorate the whole house for Christmas. Now she just needs to sort out the logistics of leaving milk and cookies for Santa (and Chex Mix for the reindeer — their favorite, she says) in a world with Covid-19.

“There’s no way we can leave them on the roof!” Madison laughed. “But maybe we can leave them outside. Santa could just drop the presents down the chimney.”

And if Santa comes through on a new baby doll for Madison after all? It will have a wardrobe ready, her mother said. The Bitty Baby that already gets tucked into bed with Madison each night is the perfect size for Madison’s preemie clothes.